Since our inception, our tagline has been “a new way of thinking.” Those words were first quoted by our founder, Ron Morgan, who was a man ahead of his time. Ron understood that one of the most important things we can teach young people is how to think in systems.

When I first met Ron, he completely changed the way I viewed myself and my role in the world. He showed me that a systems approach—dynamic, interconnected, and holistic—is far more powerful than a linear one. He pointed out that aquaponics itself is a systems-based model, and once I saw that, it changed everything about how I viewed both education and the world around me. That philosophy continues to guide everything we do at 100 Gardens today. Here is a quote from Ron Morgan regarding his feelings about modern day education:

Today’s education system is obsessed with measuring student learning through individual testing. But when it comes to how we really learn — how we work in teams, enhance group intelligence or expand community consciousness — of these things we know little or nothing.

Consider the consequences. The poor ranking of our schools and the conspicuous lack of practical skills all point of the shortcomings of the cold linear procedure we’ve come to call education. But there’s much we do know about learning. At it’s core, learning depends on language — it’s patterns and structures, both visual and verbal — and that language is the gateway to making discoveries and new connections.

What if we were to focus freshly and more carefully on language, and structure intentional and expansive conversations? And what if these conversations were to embrace the very best we can muster, connecting both human compassion and technical knowledge, so that science can properly become the

servant of our deepest human needs and aspirations? Without this reconnecting of the arts and sciences, our investments in education, no matter how vast, will continue to be futile, and the promptings of spirit will never be acknowledged. But by working together in hands-on ways while looking outward, not inward, we can create a regional network of compassionate, intelligent communities. It is this networked conversation that we call the “Intentional Web.”

The “intentional web” is what 100 Gardens seeks to create. In the near future, we will be able to connect our gardens together and foster conversations that lead to more discoveries and an expanded community consciousness. Now…how does aquaponics lend itself to systems thinking?

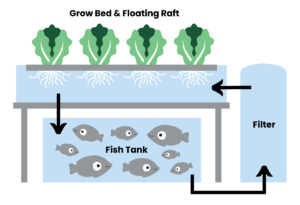

Aquaponics is a living, graphic display of how nature works. The fish provide nutrients through their waste, which feed both bacteria and plants. The bacteria convert those nutrients into a form the plants can use, and in return, the plants clean the water for the fish. It’s a perfect demonstration of balance, interdependence, and flow—the same relationships that govern our planet’s ecosystems.

Students see these connections play out every day. If they don’t feed the fish enough, the plants show nutrient deficiencies. Feed the fish too much, and the excess waste overloads the system, creating ammonia levels that can harm the fish. The lesson becomes clear: every action has a reaction within a connected web.

In my TEDx Talk, Aquaponics and a New Way of Thinking, I share another example: when students try to treat plants with traditional pesticides, those chemicals leach into the water and can harm or even kill the fish. The same thing happens in nature—pesticides sprayed on crops harm wildlife downstream, often without us realizing it. Aquaponics helps students see these consequences directly and understand how their choices ripple through entire systems.

This kind of learning leads to better problem-solving in all areas of life. When you begin to see how everything is connected, you understand the interdependence of all things. It changes how you eat, how you work, how you solve problems, and how you interact with people and the planet. Systems thinking becomes a mindset for living with awareness and responsibility.

Educators see the power of this every day. Through our curriculum, teachers connect aquaponics lessons to science, math, engineering, and environmental studies. Students don’t just memorize facts—they apply knowledge in real-world contexts, experimenting, observing, and reasoning like scientists and engineers. They begin to think broadly and dynamically rather than through memorization alone.

When you look at the condition of our ecosystems, it’s clear that humanity has had a profound impact. It’s critical that the next generation learns to think in systems, because without it, we risk repeating the same mistakes.

If you’re a parent, teacher, or community member, know that we can do something about this. We can nurture smarter, healthier, and more compassionate people—exactly what is needed to sustain both humanity and the planet we depend on.

Sam Fleming, Co-Founder and Executive Director – 100 Gardens

We’d love to hear about your approach to education and systems thinking. Reach out to us at info@100gardens.org and visit our website www.100gardens.org. If you find value in our work, consider subscribing to this blog, donating on our website, or sharing our program with a local school.